Are Wives Interesting?

On Hathaways and Others

Justice for Anne Hathaway.

Not that one. This one.

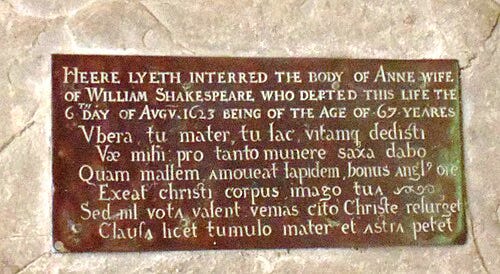

After a century of getting shat on by scholars and creatives as an illiterate adulterous cradle-robbing baby trap, Shakespeare’s government wife is being reconsidered as someone the bard might have…loved? A film adaptation of Maggie O’Farrell’s Hamnet, which portrays Anne as an earthy, soulful clairvoyant, opens this Friday to buzz of all varieties, including Oscar. In April of this year, new analysis of a letter offered evidence that Anne, long thought to have lived in Stafford for the entire course of her marriage, was a part of her husband’s artistic life in London.

This is a big reversal. For most of my life, I’ve been familiar with the Hathaway portrayed by Stephen Greenblatt (a distant, colorless burden) or James Joyce (a cheating slut)1. But to my mind, the most cutting example of Anne-tipathy was Shakespeare in Love, the 1998 movie that gave young William a muse in the form of a crossdressing blonde teenage noblewoman, with Hathaway relegated to a rueful aside.

There is something to critique in the Shakespeare in Love approach to the mysteries of genius. A real woman must have inspired these female characters, but definitely not the one the writer had three kids with. She was middle class and illiterate and older than her husband, and what kind of story can you tell about that? Better to push her aside in favor of a woman who more strongly resembles Shakespeare’s heroines because she is, just like them, entirely fictional.

But I should be clear, I’m far from pro-Anne. A marriage between 19 and 26, with a baby born 6 months after, does not reflect well on the 26 year old, no matter the century, no matter the genders. And it’s indisputable that Shakespeare maintained a Stafford household for his whole career, and almost certain they spent a significant portion of that career apart. (Otherwise why maintain the household?). The whole thing with leaving her his second-best bed in his will? Who knows what that means, but it isn’t particularly romantic. So, I get it, Shakespeare in Love. I’m not mad.

However, what the hell did Rosemonde Gérard do to deserve this treatment?

During research for my Cyrano de Bergerac chapter, I ran across a 2018 French movie that is very obviously trying to do for Edmund Rostand what Shakespeare in Love did for Shakespeare, right down to the name, Cyrano My Love. It dramatizes the writing and production of Cyrano de Bergerac in 1898 with the clear aim of telling a “muse” story, one that would connect the creation of a great love story with a great love reality.

The only problem is, when he wrote Cyrano, Rostand was married with two young children, and wives are not romantic. So, like the Shakespeare in Love team, writer/director Alexis Michalik created a new love interest, a costumer who adores Rostand’s poetry. When Rostand helps a handsome actor woo the girl, he gets a little too passionate, mix-ups ensue, and their catfishing farce ends up inspiring the plot of the soon-to-be smash hit. Again, I get it. It’s hard to mirror the plot of Cyrano with a wife, and wives are not interesting, but…

Here’s the thing. His wife, Rosemonde Gérard, WAS.

She was a poet! A recognized and published fellow poet. A playwright too— a play she cowrote was made into a movie starring Mary Pickford! I mean, check out the stats on this wiki! Sure, her work was eclipsed by her husband’s mega hit Cyrano but most mothers of 2 would be thrilled to do this well in their careers.

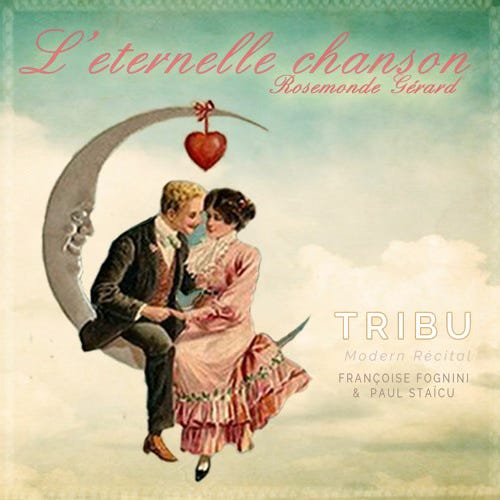

Her most enduring poem, L’eternelle chanson, became a faddish piece of jewelry:

Car, vois-tu, chaque jour je t’aime davantage,/ Aujourd’hui plus qu’hier et bien moins que demain.

(In translation, that’s “For, you see, each day I love you more/ Today more than yesterday and less than tomorrow. How this relates to “I love you more today than yesterday but not as much as tomorrow” from the song I’m not sure.)

In 1907, jeweler Alphonse Augis starting using the line on medallion necklaces, frequently shortening it to “ + qu’hier − que demain,” which is just honestly really cute and I want one.

As a screenwriter, I understand that the remit for Cyrano My Love was to show real life events mirroring the play, and it’s hard to tell a tale of hopeless, masked love between two people who are already married. But honestly… could they have tried? She was a poet, after all, an intellectual just like Rostand’s heroine Roxanne. Could she not write under assumed names? I’m not saying they could have done a “do you like Pina coladas thing” but… maybe? And even if they wanted to keep the emotional adultery plot (this IS France), could I not be told, at any point, that Rosemonde was a poet herself? That her most famous work was about ever-growing and renewing love within a committed relationship?

In the movie, when she finds out about her husband’s shenanigans, Rosemonde is understanding. He needed to reawaken his poetry. He needed to find a muse. This struck me as a lot of bullshit at the time, but I didn’t know she was a poet herself. I might have found it more believable if I had.

If Hamnet supplants Shakespeare in Love as the most acclaimed and popular Shakespeare biopic, maybe France will eventually make a Rostand biopic that gives Rosemonde some shine. I think at this point she deserves it!

I hope you enjoyed learning about a couple of literary wives. I’ve since moved on to Jay Gatsby, which means I’ll be learning more about Zelda Fitzgerald, perhaps literature’s most notorious Interesting Wife. (Well known curse, “May you marry interesting wives.”) But before that, keep an eye out for the Sherlock Holmes substack, which will probably be about agents.

For a detailed look into how the popular view of Anne has changed over the past few hundred years, check out this fascinating interview.